icon bookmark-bicon bookmarkicon cameraicon checkicon chevron downicon chevron lefticon chevron righticon chevron upicon closeicon v-compressicon downloadicon editicon v-expandicon fbicon fileicon filtericon flag ruicon full chevron downicon full chevron lefticon full chevron righticon full chevron upicon gpicon insicon mailicon moveicon-musicicon mutedicon nomutedicon okicon v-pauseicon v-playicon searchicon shareicon sign inicon sign upicon stepbackicon stepforicon swipe downicon tagicon tagsicon tgicon trashicon twicon vkicon yticon wticon fm

- العربية

- ESP

- РУС

- DE

- FR

Where to watch Schedule RT Shop RT News App Question more live

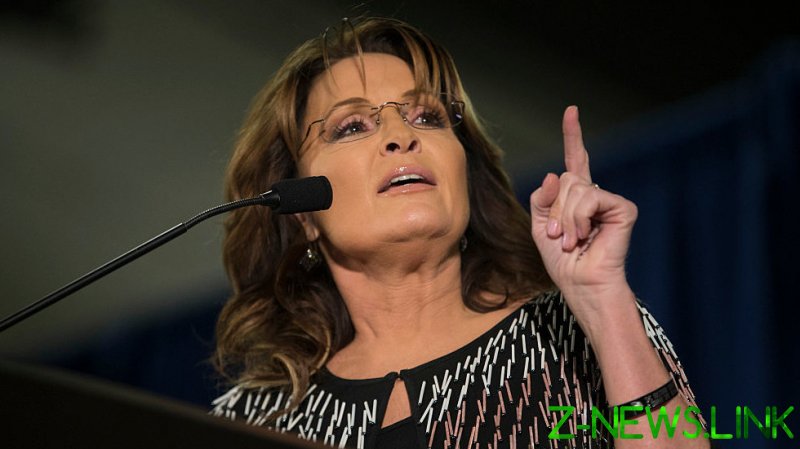

3 Feb, 2022 15:40 HomeWorld News Why Sarah Palin’s defamation case against the New York Times is important Palin says the NYT unfairly linked her campaign to a mass shooting, in a case that’ll explore where the First Amendment ends and defamation begins

Long before Donald Trump rode to office bashing the “fake news” media, former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin ran for the vice presidency channeling similar grievances against what she called the “lamestream media.”

On Thursday, a court in Manhattan will hear whether the New York Times went too far when it linked an ad published by Palin’s political action committee in 2011 with an assassination attempt on a Democratic congresswoman.

The trial was due to begin in late January, but was postponed when Palin tested positive for Covid-19.

The infamous map

Running for vice president alongside Arizona Senator John McCain, Palin missed her shot at the White House in 2008 but remained a fixture in Republican politics, staying in the media spotlight thanks to her penchant for headline-grabbing catchphrases (“How’s that hopey, changey stuff working out?” she jibed at Barack Obama’s voters in 2010), and her ascent in the then-nascent Tea Party movement.

READ MORE: Sarah Palin joins calls to pardon Assange, condemns previous comments on WikiLeaks founder: ‘I made a mistake’

Palin set up a political action committee, SarahPAC, in 2009, aimed at electing Tea Party-friendly candidates to federal and state office. The current legal showdown between Palin and the NYT began in 2010 when SarahPAC published a map showing 20 Democrat-held congressional districts the group aimed to flip to the GOP, each depicted behind crosshairs to indicate that these districts were “targeted.”

An assassination attempt

Less than a year after the map was published, Arizona Congresswoman Gabby Giffords (D) was shot in the head at a campaign event near Tucson. Giffords survived, and a police investigation found that the gunman, Jared Lee Loughner, had developed a fixation on Giffords since 2007 and had planned for some time to murder the congresswoman.

Although no link was found between the shooting and Palin’s map, Giffords – whose district was featured in the graphic – had complained about it before. “The way that she has it depicted has the crosshairs of a gun sight over our district, and when people do that, they’ve got to realize there are consequences to that action,” she told MSNBC in 2010.

A ‘clear’ link to violence?

Cones, police tape and emergency medical bags are seen at Eugene Simpson Stadium Park where House Majority Whip Steve Scalise was shot during baseball practice in Alexandria, Virginia, June 14, 2017 © Getty Images / Bill Clark

Cones, police tape and emergency medical bags are seen at Eugene Simpson Stadium Park where House Majority Whip Steve Scalise was shot during baseball practice in Alexandria, Virginia, June 14, 2017 © Getty Images / Bill ClarkThe controversy was forgotten until 2017, when a left-wing extremist opened fire on Republicans practicing in Virginia for the annual Congressional Baseball Game. Louisiana Rep. Steve Scalise (R) was wounded, and the attack was described as “an act of terrorism” by Virginia prosecutor Bryan Porter.

The New York Times published an editorial on the day of the shooting entitled ‘America’s Lethal Politics’, which connected mass shootings to the climate of political incivility in the US. In one paragraph, the Times’ editorial board argued that “the link to political incitement was clear” between Palin’s ad and Giffords’ shooting, after falsely describing the map as featuring Democratic lawmakers’ faces behind crosshairs, not just their districts.

Conservatives were outraged, and even the liberal-leaning Washington Post fact-checked the article and called the claim “bogus.” The Times corrected the paragraph to read that “no connection to the shooting was ever established” and revised its description of the map.

Palin was not satisfied, and she sued the New York Times two weeks later.

Mistake or malice?

For the Times to be found guilty of defamation, Palin must prove that the newspaper acted with “malice,” as opposed to making a mistake. That standard was set out in another landmark case involving the Times: 1964’s New York Times v. Sullivan.

“In our view, this was an honest mistake,” David McCraw, the Times’ deputy general counsel, told The Washington Post in 2019. “It was not an exhibit of actual malice.”

In fact, Palin’s case was initially dismissed in 2017, but she successfully appealed and it was allowed to move forward.

While Palin’s attorneys have stayed silent in the runup to the trial, they previously attempted to prove this “malice” by drawing attention to the fact that James Bennet, who inserted the allegedly libelous paragraph into the 2017 editorial, had previously edited at The Atlantic, which published salacious stories suggesting that Palin may have lied about the birth of her disabled child.

Sarah Palin holds her son Trig Palin as she speaks during a rally for the Tea Party Express national tour in Phoenix, Arizona, October 22, 2010 © Getty Images / Joshua Lott

Sarah Palin holds her son Trig Palin as she speaks during a rally for the Tea Party Express national tour in Phoenix, Arizona, October 22, 2010 © Getty Images / Joshua LottPredicting an outcome

Palin is seeking more than $400,000 in damages, but she faces an uphill battle. The definition of defamation laid out in New York Times v. Sullivan remains the law of the land, and was even enshrined in New York law in 2020 as the standard for nearly all libel cases involving public policy disputes.

In the Sullivan case, the Times was found not guilty of defamation, even though it had published a full-page advertisement by supporters of Martin Luther King in which false claims were made about prominent officials in the South, accusing them of violating the civil rights of African Americans.

READ MORE: Former GOP vice president candidate on Covid-19 vaccine: ‘Over my dead body’

However, the trial will still bring unwanted attention to the New York Times, which in recent years has been accused of partisanship. Several weeks before publishing the 2017 op-ed, the Times did away with its public editor, or ombudsman. The last journalist to hold this position, Liz Spayd, said at the time that her firing suggested the mainstream media was about to “morph into something more partisan, spraying ammunition at every favorite target and openly delighting in the chaos.”

Palin’s lawyers will likely also press Bennet on his resignation – at the behest of other writers – in 2020 over the publication of an editorial by Republican Senator Tom Cotton (Arkansas) calling on then-President Donald Trump to “send in the troops” against Black Lives Matter rioters. The implication here, of course, is that when an editor is forced to resign for publishing a conservative op-ed, the paper must be inherently biased to the left.

The trial is expected to last a week. With Palin likely to testify against Bennet, it will also garner significant media attention.

© 2022, paradox. All rights reserved.