Kissinger this week warned that potential conflict arising from the deteriorating ties between the two countries could be far more catastrophic than in the original Cold War itself, describing them as “the biggest problem for America, the biggest problem for the world.”

How so, one may ask? Didn’t the first Cold War bring with it threats of immense destruction in the possibility of mutual nuclear conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union? How might this one be worse? Kissinger, speaking at a webinar with the McCain Institute’s Sedona Forum, argued that, despite such parallels, advances in technology mean that the two countries’ capabilities to destroy each other, and with that the rest of the world, are far more severe than those of the 1960s or 1970s.

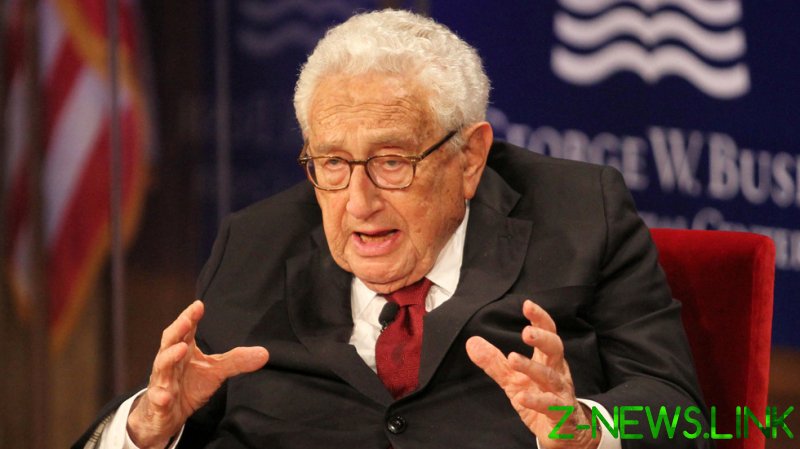

“For the first time in human history, humanity has the capacity to extinguish itself in a finite period of time,” Kissinger, 97, a former US Secretary of State, said, pointing out that to “the nuclear issue is added the high tech issue, which in the field of artificial intelligence, in its essence is based on the fact that man becomes a partner of machines and that machines can develop their own judgement.” This is not just about nuclear missiles, as it was in the days of America and the Soviet Union, but also about the ability of advanced technology to reimagine and refine warfare in ways not conceived previously.

But how likely is a conflict? And how might it emerge? At present, the United States sees itself embroiled in a “strategic competition” with China “for the 21st century.” The foreign policy objectives the Biden administration have set are long term, as opposed to short term. It centers around sustaining American hegemony through grouping together with “like-minded countries” and seeking to uphold strategic primacy over core technologies, values and, of course, a “free and open Indo Pacific.” Although it has tried to play down the idea that these ideas constitute “containment,” it’s hard to see them in any other way.

On the other hand, China is seeking to complete what Xi Jinping has described as “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” which centers round the restoration of the country to a status it once held. Now, while this does not specifically mean “hegemony” over the world as a whole, what it does mean is that the inevitable ascendancy of China as a technological, economic and military power all are prerequisites to complete its vision of development. This also includes, of course, restoring the disputed sovereign claims it perceives to have lost, including Taiwan and the South China Sea. This inevitably puts it on a collision course with American strategic interests, which fears a change in the global balance of power.

Whereas competition among powers is one thing, the probability of a war itself rests on a scenario whereby either side sees no other option, and is compelled to that course of action as a last resort. Policies of strategic competition can quickly escalate into armed conflict. In today’s world, however, war is never a “first resort” between great powers; hence the Soviet Union and the United States adequately managed their differences to avoid one.

Likewise, it is difficult to say in today’s vastly interdependent and connected world, that conflict between the US and China could be a voluntary choice. However, there are a number of “flashpoints” which ultimately create the probability for conflict, and one more volatile than those envisaged during the original Cold War.

Take Taiwan, for example. China’s first and preferred option for the territory is “peaceful reunification” – a consensual agreement between Taipei and Beijing. Yet, for an issue they prioritize so much, that seems almost a non-starter right now. China of course, has never ruled out the use of force, but as countries such as the United States aim to slowly increase support for Taiwan, what happens next?

What happens if Beijing starts to feel alienated and fearful of growing military encirclement by the west, and perceives the issue is slipping away from it? China could decide to make a calculated gamble assuming that it could quickly seize the island before Washington and others could ready a response, only for things then not to go according to plan?

Major conflicts are often brought about by such ill-placed gambles and miscalculations feeding into flawed assumptions about the behaviour of the other side. That’s why right now, in US foreign policy circles, there is an ongoing debate as to whether the United States should sustain “strategic clarity” or “strategic ambiguity” in the event of a Taiwan invasion.

The discussion centers on whether an open US commitment to Taiwan would be stabilizing or destabilizing, particularly in the wake of Beijing upping its military activities around the island. Might a US declaration of military commitment to Taipei force China into responding, or might staying silent make Beijing try its luck in the future? Crucially, the Pentagon’s own war games suggest the US would be defeated if it did intervene in such a scenario.

Kissinger ultimately makes the point that the United States and China have to learn to co-exist and compromise. He, of course, is a relic from a different “strategic era”– one where Washington openly embraced and engaged Beijing, starting from the 1970s, in order to counter, quite ironically, the threat of the USSR.

Yet increasingly, as was the case with that Cold War, the risk of an accidental or miscalculated conflict is real and, right now, it is growing. What the world needs to understand is that the potency for destruction, involving a China which is larger, more economically and technologically advanced than the Soviet Union was, makes the potential outcome much graver.

So is a new Cold War truly the best choice for managing this relationship? One with more openly volatile flashpoints than the original? Strategic restraint, not containment, might be the better answer.

Like this story? Share it with a friend!

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

© 2021, paradox. All rights reserved.